Cecropia pachystachya – Ambay pumpwood

"Every naturalist who has been in tropical America will remember Cecropia, belonging to the most conspicuous trees of those countries". (Schimper, 1888: 26)

|

| Cecropia pachystachya and I<3. Image by Tan Koon Ngee Jonathan. |

Cecropia is a genus of pioneer trees which are common and ecologically important in the humid environments of the Neotropics where they are native to.

[1] Owing to their fast growth and ability to form alliances with aggressive ants, numerous

Cecropia species are not only hardy survivors but also successful invaders of the Palaeotropics.

[1] [2] In Singapore,

Cecropia pachystachya has infested many green spaces, leading to concerns about the displacement of native ecological analogues such as

Macaranga species.

[2]

Invasiveness

Some

Cecropia species, including

Cecropia pachystachya, are considered weeds.

[1] The ability to grow fast, reproduce independently of animal pollinators and continuously produce persistent, wide-spreading and plentiful seed banks (refer to sections on pollination, dispersal, and flowering and fruiting in "Ecology" below for more details) enables

Cecropia species to invade unexplored territories. Over the past few decades, several

Cecropia species have been introduced in the Palaeotropics, including West Africa, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, and they have naturalized and spread widely in these countries of introduction.

[2] [3] [4] Notably,

Cecropia peltata is part of IUCN's "100 of the world's worst invasive alien species".

[5] Even without its ant associates,

Cecropia peltata in Malaysia were found to outgrow native pioneer trees such as

Macaranga gigantea.

[3] On the other hand,

Cecropia pachystachya has successfully reproduced and colonized large areas in Rarotonga of the Cook Islands, where it is regarded as seriously invasive, and in Singapore and West Java where it is at 'high-risk' of being invasive.

[4] [6] More long-term studies are required to ascertain whether

Cecropia pachystachya impedes the growth and survival of other plants in the latter two countries.

Distribution

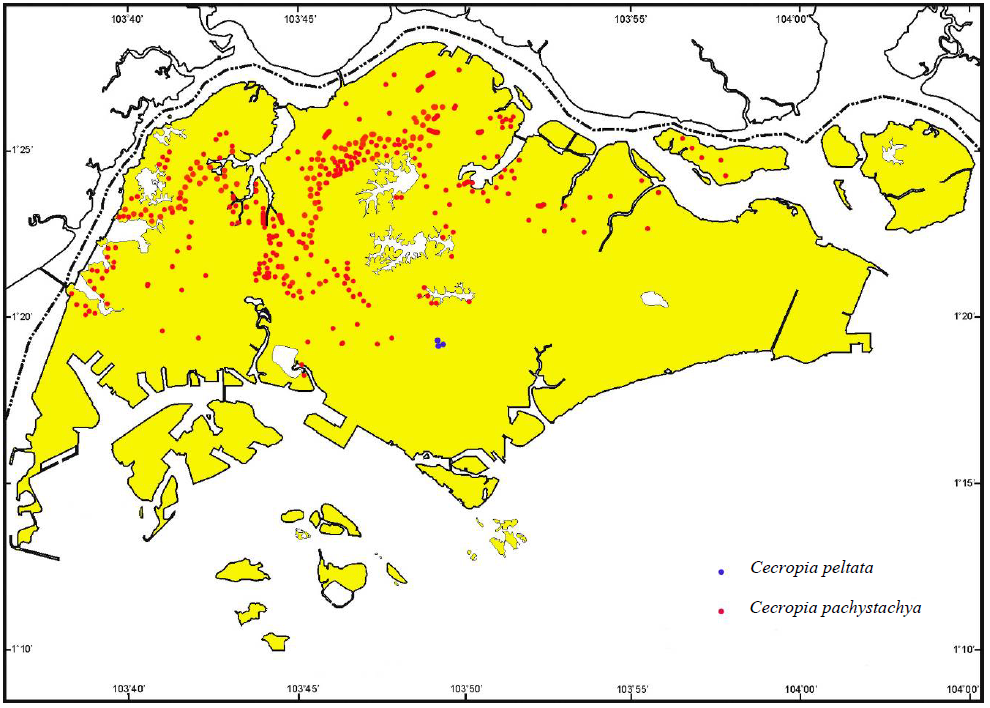

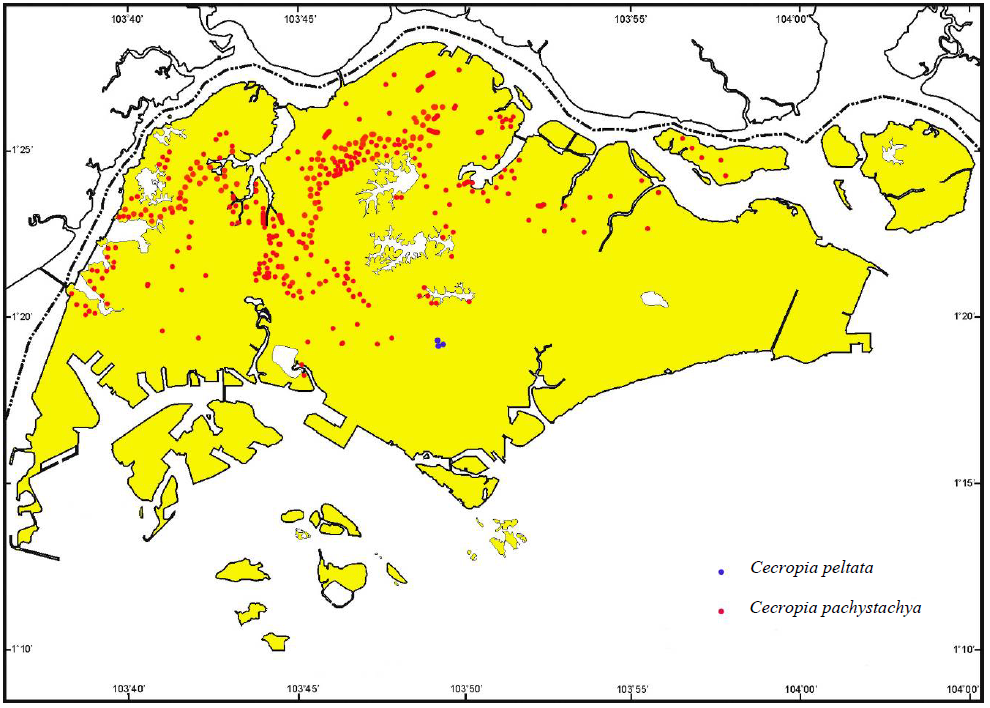

Within Singapore,

Cecropia pachystachya has populations established in many areas (particularly at the northern and western part of the island) and is colonizing more areas.

[2] This species might have been introduced into the country when the Singapore Zoo imported them in 1992 as food for sloths.

[2]

|

| Distribution of Cecropia peltata and Cecropia pachystachya in Singapore. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

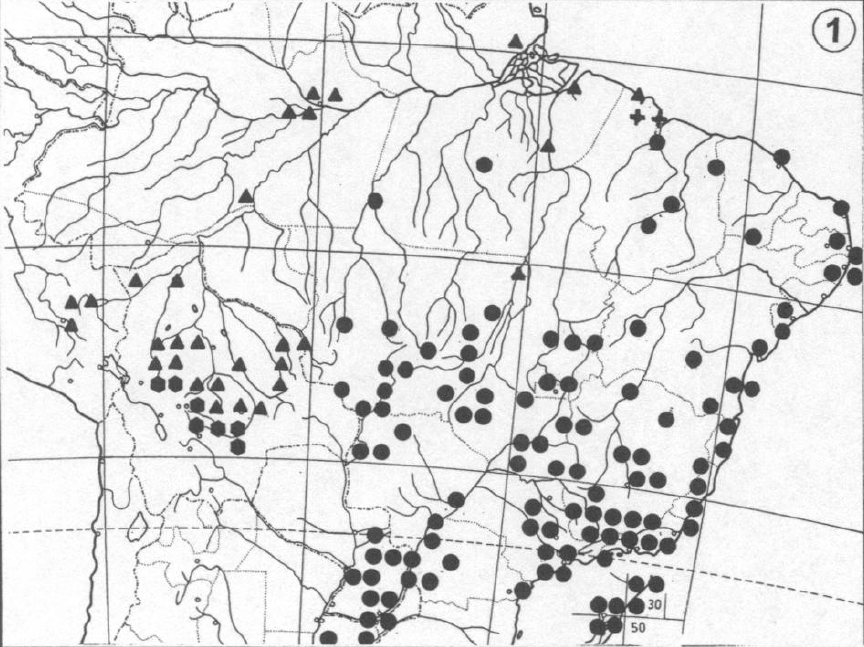

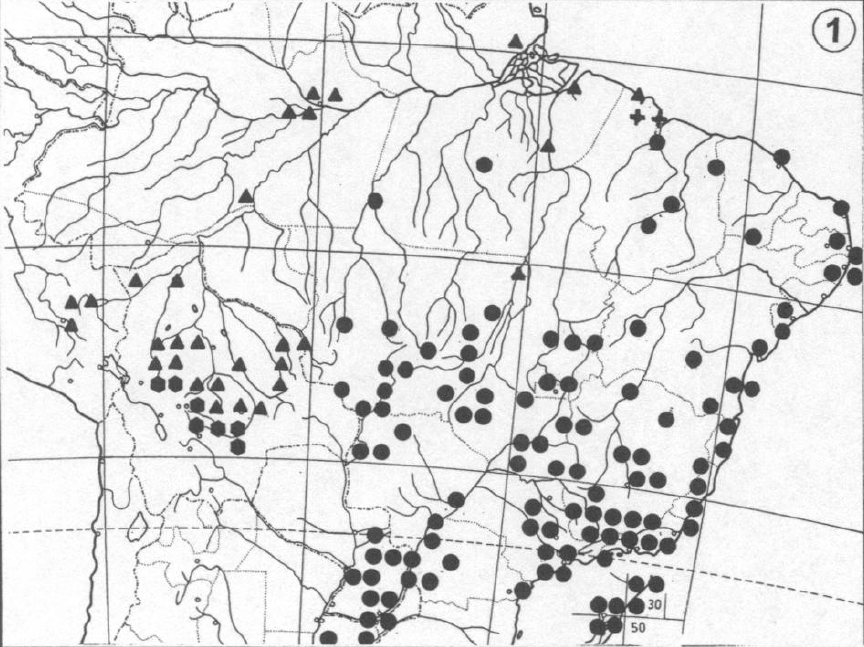

The native range of

Cecropia pachystachya is in central and eastern Brazil, from as far as the southern edges of the Amazon basin to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

[1]

|

| Native distribution of Cecropia pachystachya (marked by circles and crosses on the map). Image from Berg et al., 2005. |

Ecology

Pollination

Cecropia pachystachya is predominantly wind-pollinated. Wind-induced motion of the spikes easily releases copious amounts of dry pollen.

[1] Though unproven, insects such as small beetles and flies that breed in the staminate inflorescences possibly facilitate pollination.

[7] [8]

Dispersal

Mature individuals can produce millions of seeds which are effectively dispersed (possibly a few kilometers) by birds such as Toucans and various insectivorous birds in the Neotropics, fruit bats, monkeys, opposums and even fish.

[1] In Singapore, the fruits have been observed to be consumed by good dispersers of seeds–various frugivorous and generalist bird species such as the yellow-vented bulbul (

Pycnonotus gaoivier), common myna (

Arcidotheres tristis) and the Philippine glossy starling (

Aplonis panayensis), as well as the lesser dog-faced fruit bat (

Cynopterus brachyotis).

[2] Moreover,

Cecropia seeds can remain viable in the soil for long periods of time–potentially more than five years–under the right conditions and germinate opportunistically when conditions are favorable, i.e., exposed to full sunlight and fluctuating temperatures.

[9] [10]

| | Yellow-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus gaoivier) at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, Singapore. Image by Yap Lip Kee, licensed under Creative Commons. |

|

| | A common myna (Arcidotheres tristis) in Sydney Park, Australia. Image by Richard Taylor, licensed under Creative Commons. |

|

| | Asian Glossy Starling (Aplonis panayensis) in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Image by Yap Lip Kee, licensed under Creative Commons. |

|

| | Lesser dog-faced fruit bat (Cynopterus brachyotis) in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. Image by Anton Croos, licensed under Creative Commons. |

|

Flowering and fruiting

Cecropia pachystachya flowers and produces fruits freely throughout the year on a population level but intermittently on an individual basis.

[1] As a result, the species can be an important food source for frugivores.

[11] A study of the phenology of tree species in Brazil reported that the flowering and fruiting of

Cecropia pachystachya lasted for four months and two months respectively.

[12]

Ant associations

Around 80% of the species in the

Cecropia genus, including

Cecropia pachystachya, have mutualistic associations with ants.

[7] Such plants are called myrmecophytes.

Cecropia-associated ants belong to the

Formicidae family, with the

Azteca genus being the most prevalent and well-known group.

Cecropia pachystachya has evolved obvious coadaptations such as hollow stems, prostomata and Müllerian bodies (refer to section on branches in "Description and identification" below for picture and explanation) to provide ants with a secure home and nutritious food. In return, the ants protect their host plants against herbivores and stem borers (especially beetles), as well as vines and other plants that compete with the hosts for resources.

[1] Since

Azteca ants are not found in Singapore and native ants species have yet to develop specialized associations with

Cecropia pachystachya, it is possible that the species has not reached its maximum invasive ability.

[2]

Uses

In their native range,

Cecropia species are used in the following ways:

- Decoctions of leaves are taken as a cardiac stimulant, antiasthmaic, antipneumonia, antidiabetic and diuretic.[1]

- Leaves are made into plasters and applied to swellings.[1]

- Wood can be processed into caskets, matches and rafts.[1]

- Root extracts are used to aid the recovery of wounds, inflammation on the skin and blisters.[1]

- Spikes are eaten and sold as food.[1]

Description and identification

On the island of Singapore,

Cecropia pachystachya commonly infests disturbed secondary forests and tends to be concentrated at the edges of green spaces. The following features can be used to identify the tree.

General form

Cecropia pachystachya is a tree that can grow up to 12m tall. It has whitish to greenish leafy twigs that are one to 4cm thick. It is also dioecious, meaning that each tree has either staminate (male) inflorescences only or pistillate (female) inflorescences only.[1]

|

| | Cecropia pachystachya tree. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

|

Leaves

The entire leaves are typically shaped like a palm and often separated into nine to 13 finger-like segments. Each segment has a narrow oval shape that tapers to the base but some segments can be almost egg-shaped. Moreover, the leaf edges have wave-like indentations or lobes. For the itchy fingers, the rough and hairy leaf blades feel papery to slightly leathery.[1]

|

| | Cecropia pachystachya sapling with leaves clearly shown. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

|

Branches

At the base of the leaf stalk, there is a dense patch of hairs called trichilia which serves as a prickly defense for the plant. The trichilia comprise of 1) long, white unicellular hairs (also known as trichomes), 2) short, stiff, brown pluricellular hairs, and strangely, 3) Müllerian bodies which are food rewards, containing lipids, proteins and glycogen, for ants.[1] The stems are hollow and sport prostomata (singular: prostoma), weakened sites in the stem walls where some ants recognize and chew through so that they can use the hollow parts of the stems as their home.[1]

|

| | A dense patch of hairs at the base of the leaf stalk of Cecropia pachystachya. Several features have been labelled. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

|

Roots

Adventitious roots (those growing from the stem), which later develop into prop roots, are found in Cecropia pachystachya and all other Cecropia species. These are particularly visible for larger trees or trees that grow in the soft substrate near streams or marshes.[2]

|

| | Prop roots of Cecropia pachystachya. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

|

Staminate (male) inflorescences

The hairy, staminate inflorescence-bearing stalk ranges from five to 17cm long and can be straight or curved. The whitish to pale greenish sheath enclosing the staminate inflorescence is three to 18cm long. The outer surface of the sheath is hairy while the inner surface is hairless. The pale yellow spikes have five to 20 segments that hang down loosely.[1]

|

| | Staminate inflorescences of Cecropia pachystachya. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

|

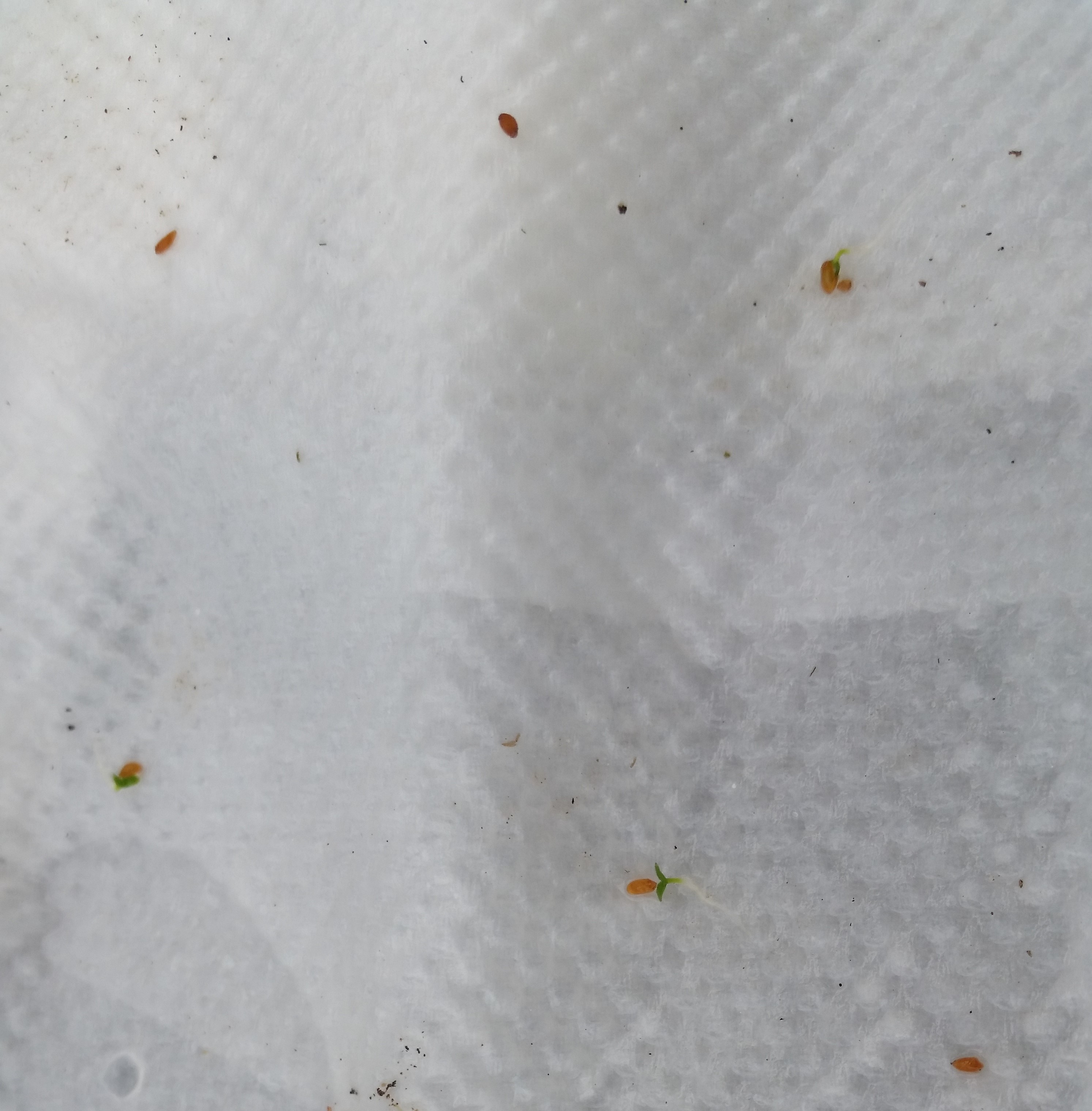

Pistillate (female) inflorescences

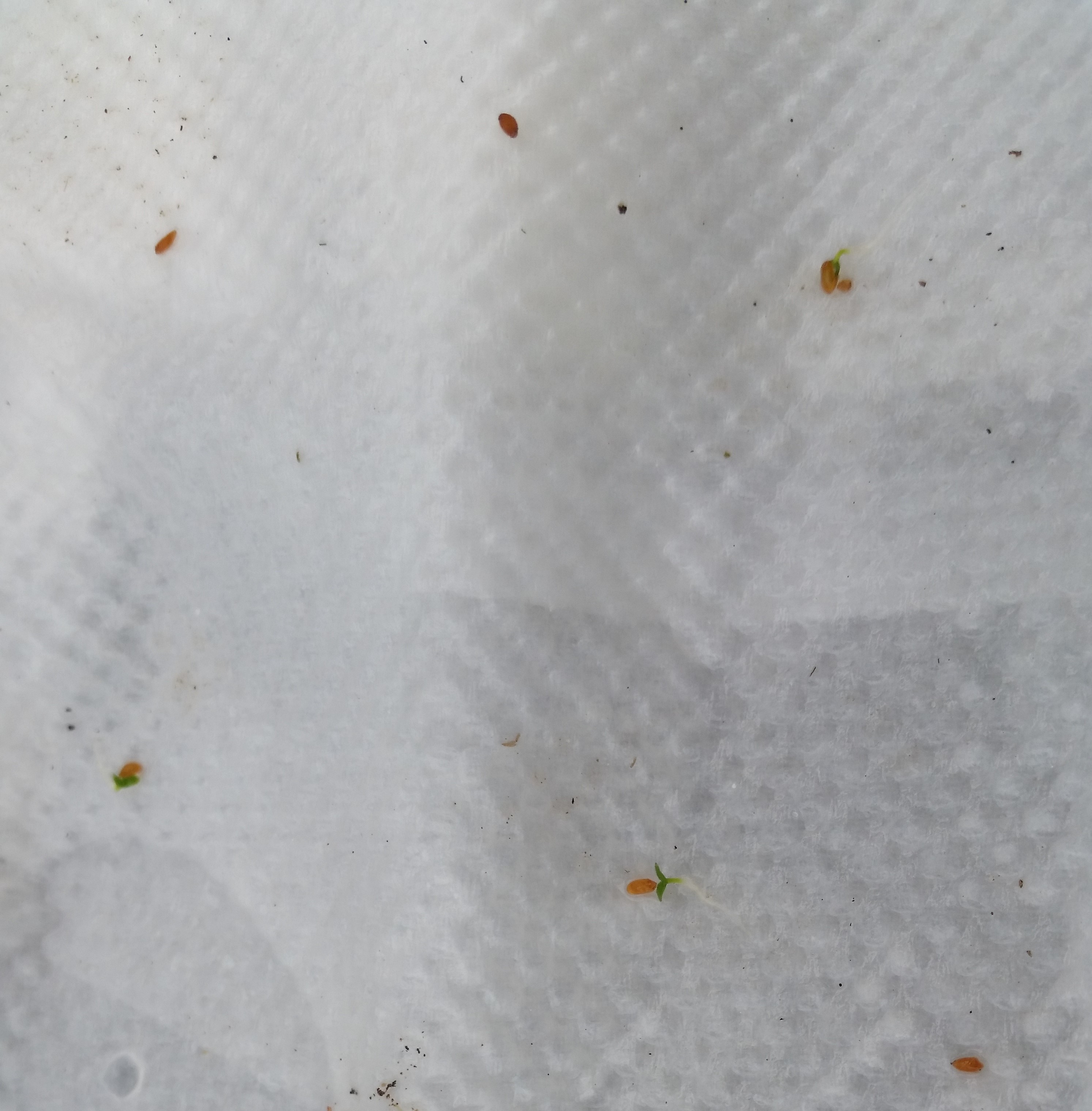

The hairy, pistillate inflorescence-bearing stalk ranges from four to 15cm long. The sheath enclosing the pistillate inflorescence has a colour and hair features that are similar to that of the staminate inflorescence, but is three to 10cm long. The spikes have three to eight elongated, brownish segments covered with small rounded nodules which turn green when ripe. Spikes contain many fruits which are individually around two to 2.2cm long.[1] [6] Each fruit contains one seed which is about 1mm long.[6] [13]

|

| | Pistillate inflorescences of Cecropia pachystachya. Image by Alvin Francis Lok Siew Loon. |

| | Cecropia pachystachya seeds germinating on a piece of wet tissue paper. Image by Tan Koon Ngee Jonathan. |

|

Taxonomy

Nomenclature

Etymology

Cecropia is derived from Cecrops, the name of the mythical king of Attica, a historical region within which Athens now stands. Cecrops is often depicted as half-man and half-serpent.

[14] This might have inspired one of the vernacular (or common) name of

Cecropia species, snakewood.

[1]

|

| Depiction of Cecrops. Image, in the public domain, from the 4th edition of Meyers Konversationslexikon (1885–90). |

Pachystachya could possibly be broken down into pachys, which is greek for thick or stout, and stachys, which is greek for spike.

[15]

Synonyms

When a species has many names, also known as synonyms, information on that species can no longer be retrieved precisely. If you are conducting research on

Cecropia pachystachya and publishing your results to a database, kindly use the accepted name,

Cecropia pachystachya, and avoid using the following synonyms

[16] [17] :

- Ambaiba adenopus (Mart. ex Miq) Kuntze

- Ambaiba carbonaria (Miq.) Kuntze

- Ambaiba cinerea (Miq.) Kuntze

- Ambaiba crytostachya (Miq.) Kuntze

- Ambaiba lyratiflora (Miq.) Kuntze

- Ambaiba lyratiloba (Miq.) Kuntze

- Ambaiba pachystachya (Trécul) Kuntze

- Ambaiba tenoreana (Ten. ex Miq.) Kuntze

- Cecropia adenopus Mart. ex Miq.

- Cecropia adenopus var. lata Snethl

- Cecropia adenopus var. lyratiloba (Miq.) Hassl.

- Cecropia adenopus var. macrophylla Hassl.

- Cecropia adenopus var. oblonga Snethl.

- Cecropia adenopus var. vulgaris Hassl.

- Cecropia ambaci Rojas

- Cecropia carbonaria Miq.

- Cecropia catarinensis Cuatrec.

- Cecropia cinerea Miq.

- Cecropia crytostachya Miq.

- Cecropia digitata Ten. ex Miq.

- Cecropia glauca Rojas

- Cecropia lyratiloba Miq.

- Cecropia lyratiloba var. nana J.C.Andrade & Carauta

- Coilotapalus peltata Britton

Scientific classification

The taxonomic hierarchy for

Cecropia pachystachya is as follows

[18] :

Kingdom

|

Plantae

|

Subkingdom

|

Viridiplantae

|

Infrakingdom

|

Streptophyta

|

Superdivision

|

Embryophyta

|

Division

|

Tracheophyta

|

Subdivision

|

Spermatophytina

|

Class

|

Magnoliopsida

|

Superorder

|

Rosanae

|

Order

|

Rosales

|

Family

|

Urticaceae

|

Genus

|

Cecropia

|

Species

|

Cecropia pachystachya

|

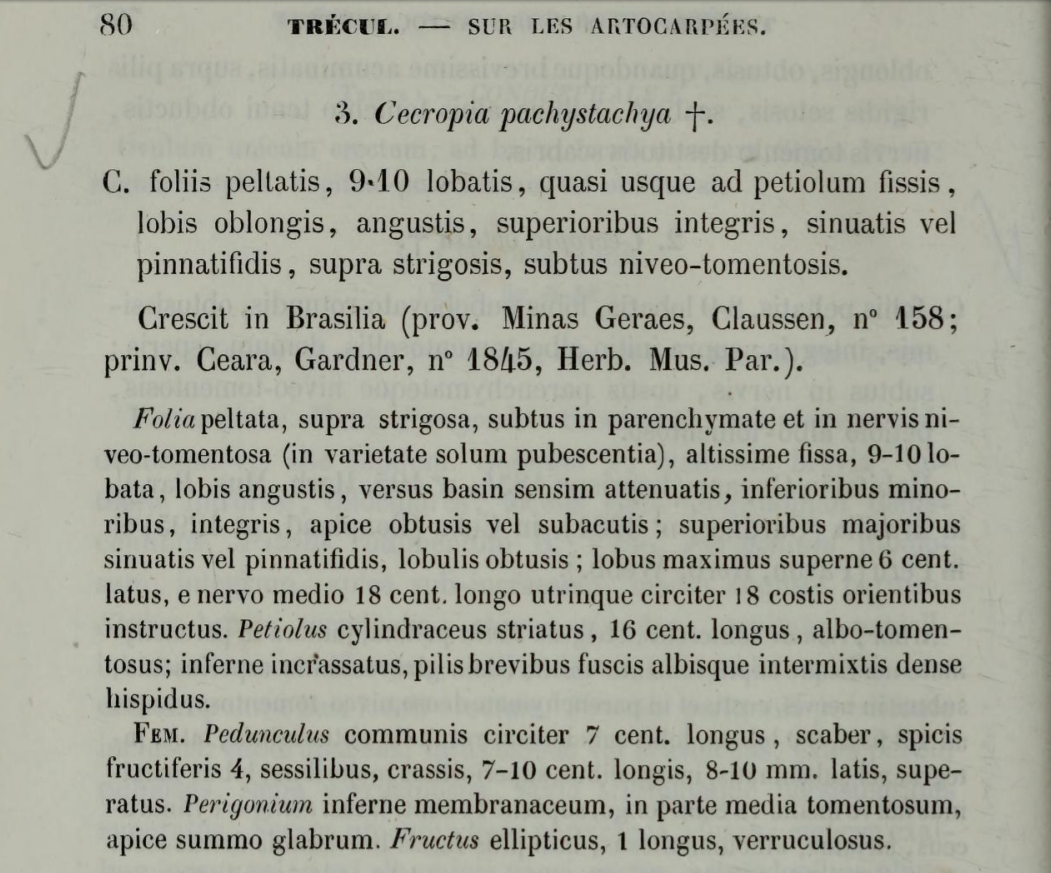

Original description

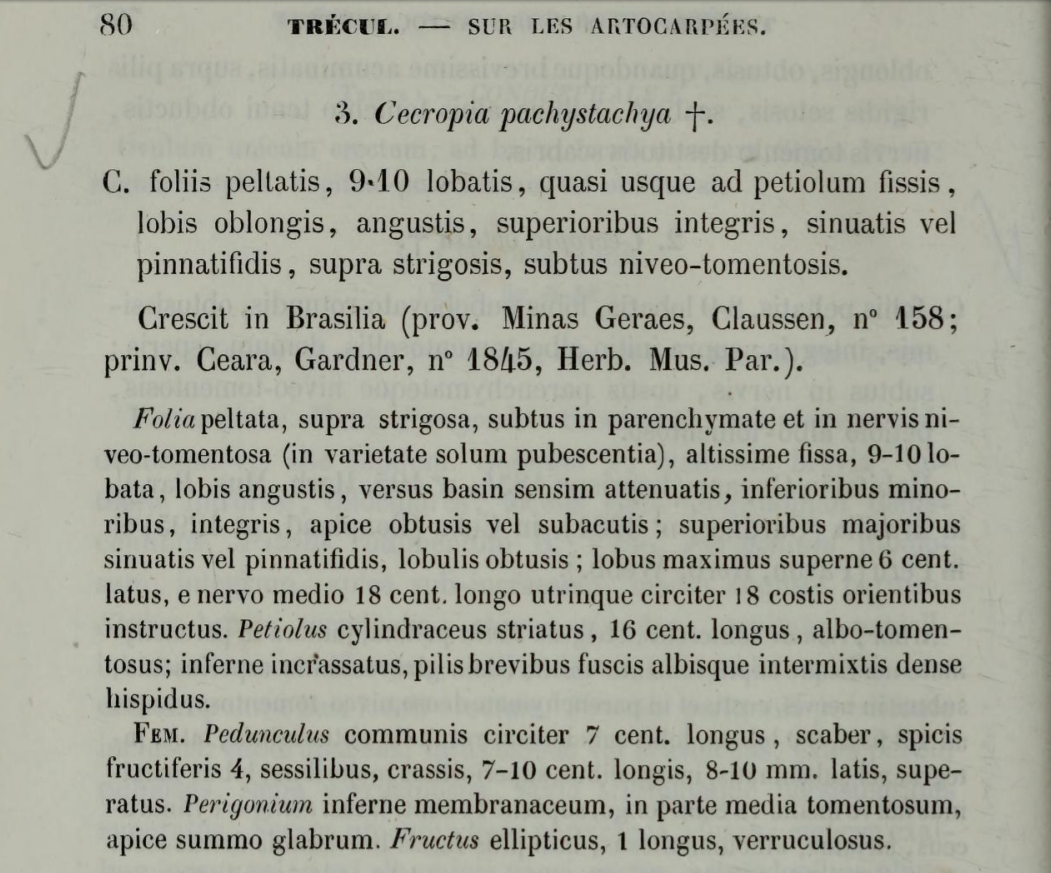

Cecropia pachystachya was described by french botanist Auguste Adolphe Lucien Trécul in 1847 in page 80 of the Annales des sciences naturelles.

|

| Original description of Cecropia pachystachya at page 80 of Annales des sciences naturelles. ser.3:t.8 (1847). Image from Natural History Museum Library, London. |

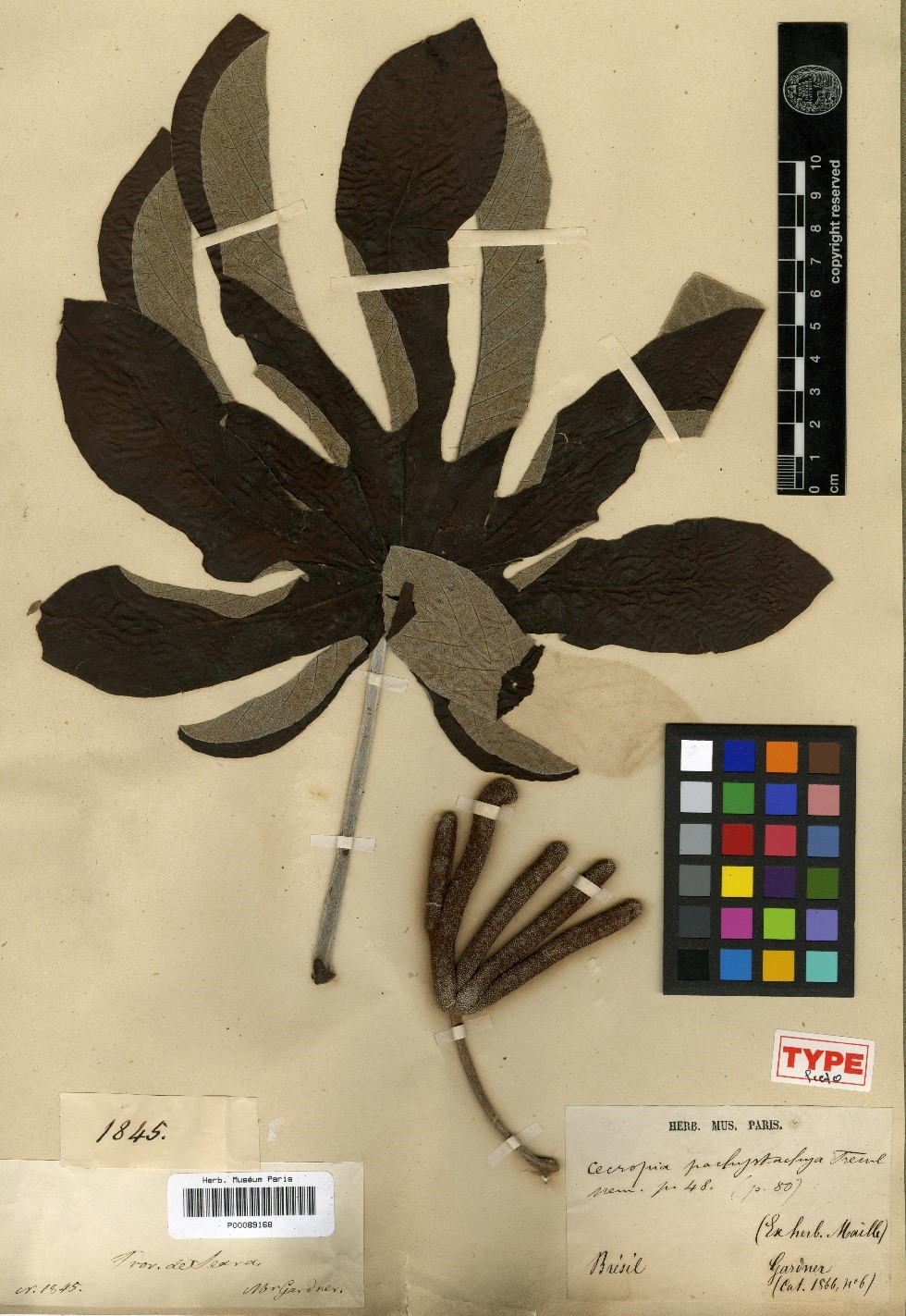

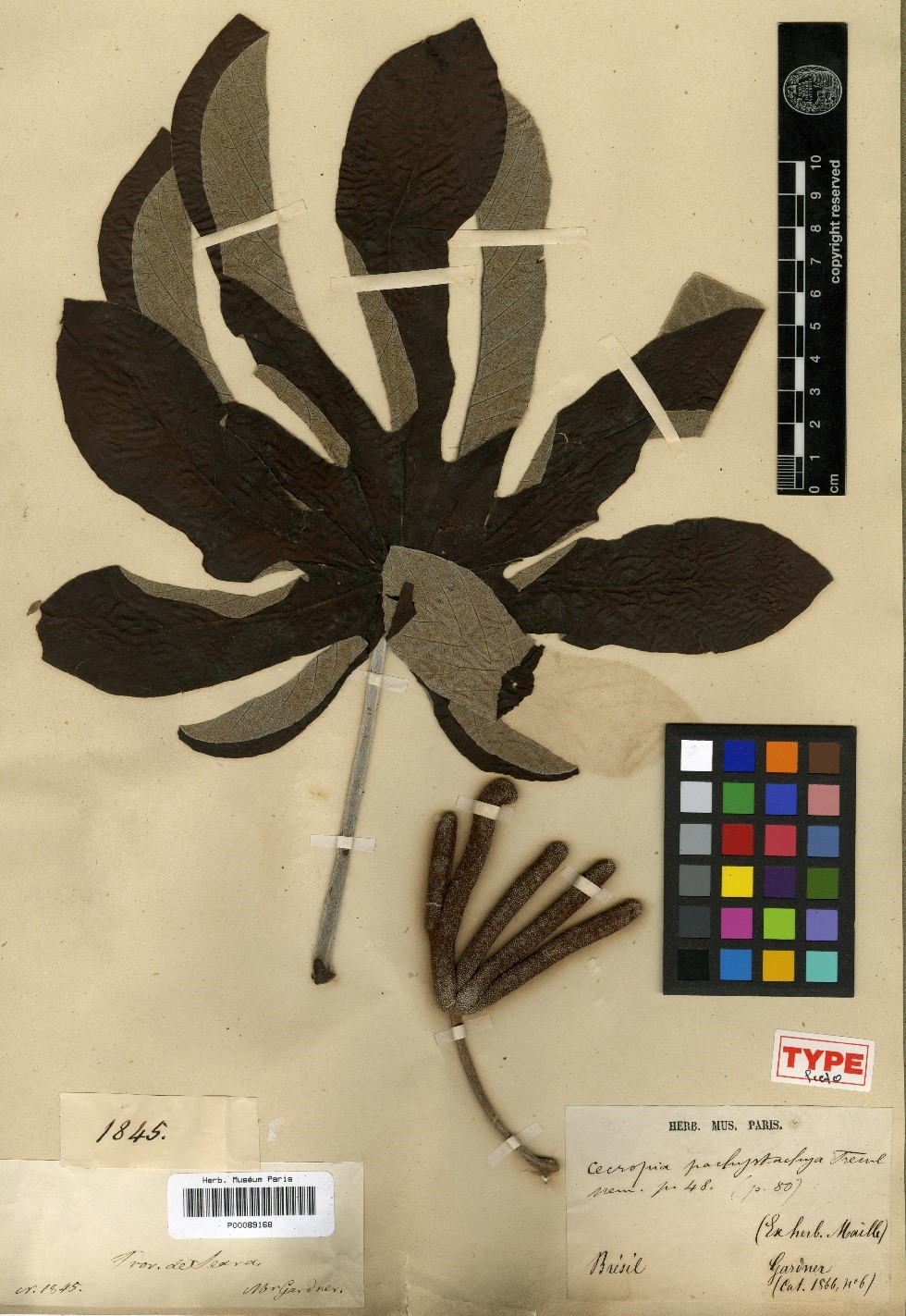

Type information

The

Cecropia pachystachya specimen collected by G. Gardner in 1840 was designated as the lectotype (a syntype chosen to be binding) by C. C. Berg & P. Franco in 2005.

[1] As

Cecropia species can be very similar in form, many

Cecropia collections mix specimens of more than one species in their mounts and researchers are gradually correcting these mistakes.

[1]

|

| Cecropia pachystachya specimen collected by G. Gardner (collector's number: 1845) in 1840. Image from Musuem National d'Histoire Naturelle. |

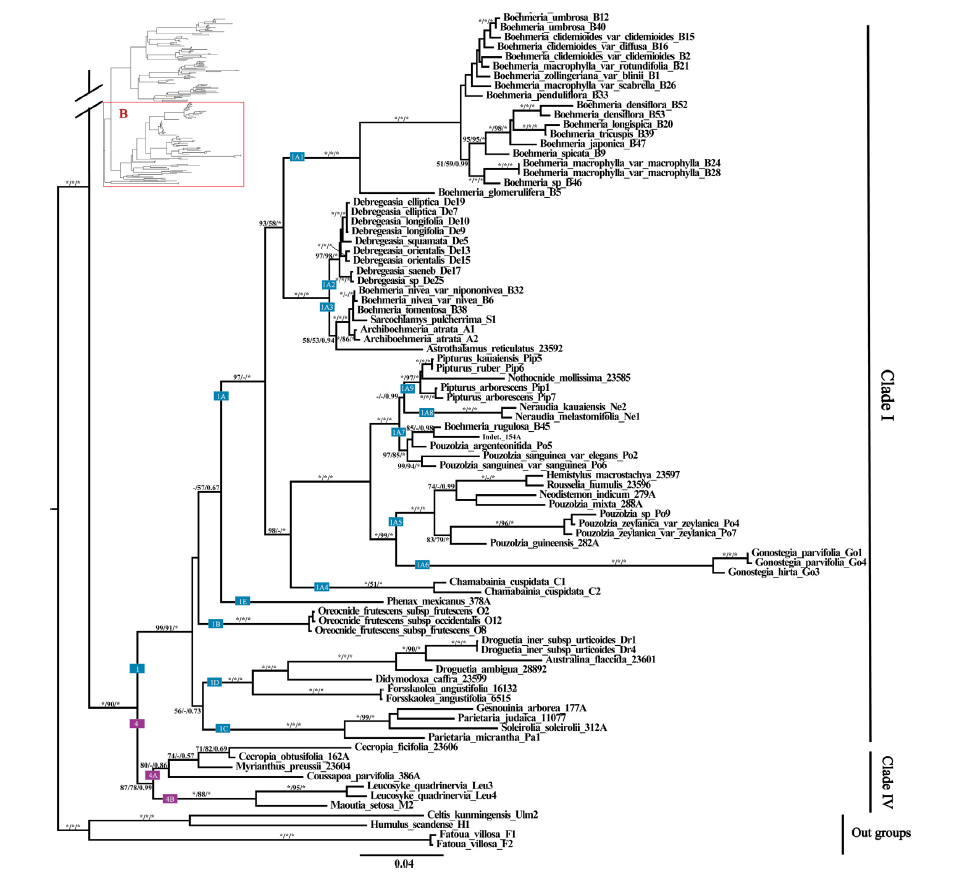

Phylogeny

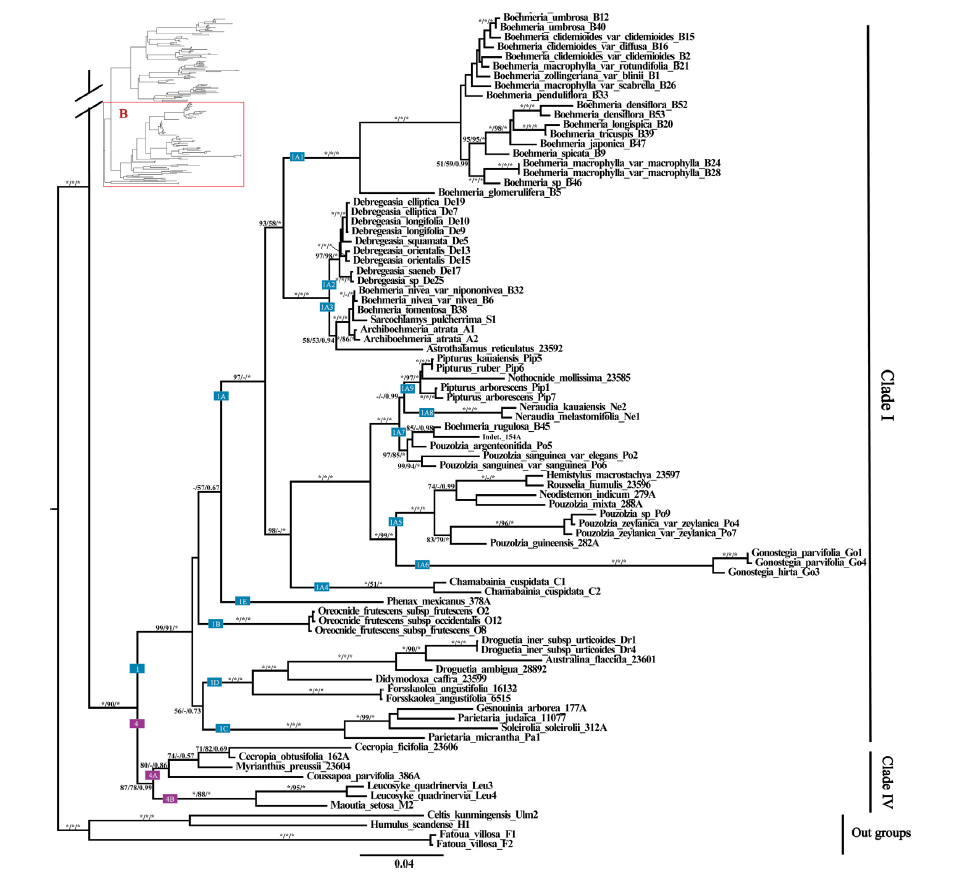

Cecropia species were previously grouped under Cecropiaceae, which was deemed distinct from Urticaceae based on morphological characters such as the stamens filaments in the bud being almost always straight rather than bending outwards and the lack of a herbaceous growth form. However, a recent phylogenetic analysis involving 122 species (47 genera) in Urticaceae, including four genera sometimes considered under Cecropiaceae (one of which is

Cecropia), showed that Cecropiaceae had two lineages which were both nested in Urticaceae (see phylogenetic tree below). This indicates that the

Cecropia genus should be included under the Urticaceae family. There was also high support that Urticaceae plus Cecropiaceae forms a monophyletic clade. These results were derived from maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony and Bayesian inference analyses on the DNA sequences from two nuclear loci (ITS and 18S), four chloroplast regions (matK, rbcL, rpl14-rps8-infA-rpl36, trnL-trnF) and one mitochondrial gene (matR) of the species studied.

[19] They are in congruence with the results of previous molecular studies on the phylogeny of Urticaceae (maximum parsimony analysis based on chloroplast DNA sequences of trnL-F and rbcL) and Urticalean rosids (maximum parsimony analysis applied to trnL-F, rbcL and ndhF plastid regions).

[20] [21] There is much evidence for the merging of Cecropiaceae, and therefore

Cecropia, into Urticaceae.

|

| Figure 1 from Wu et al., 2013 showing a "Phylogenetic tree produced by Bayesian Inference analysis based on the matrix with plastic, mitochondrial, and nuclear datasets combined, considering those clades with bootstrap BP more than or equal to 50%, and posterior probability more than or equal to 0.6, respectively. Clades are referred by numbers in the box; Numbers associated with branches are assessed by Maximum Likelihood Bootstrap, Maximum Parsimony Bootstrap and Bayesian posterior. "–" shows no support, "*" means fully support (100%/1.00). Numbers following species name denote the lab codes." |

References

Quote:

Schimper, A. F. W. 1888. Die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Pflanzen und Ameisen im tropischen Amerika. Bot. Mitt. Tropen 1: 1-95.

- ^ Berg, C.C., Rosselli, P.F. and Davidson, D.W., 2005. Cecropia. Flora Neotropica. 1-230.

- ^ Lok, A.F.S.L., Tan, K., Chong, K.Y., Nghiem, T.P.L. and Tan, H.T.W., 2010. The distribution and ecology of Cecropia species (Urticaceae) in Singapore. Nature in Singapore. 3: 199-209.

- ^ Putz, F.E. and Holbrook N.M., 1988. Further observations on the dissolution of mutualism between Cecropia and its ants: the Malaysian case. Oikos. 53: 121-125.

- ^ Conn, B.J., Hadiah J.T. and Webber L.B., 2012. The status of Cecropia (Urticaceae) introductions in Malesia: addressing the confusion. Blumea. 57(2): 136-142.

- ^ Lowe, S., Brown M., Boudjelas S. and De Poorter M., 2000. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) a specialist group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN). 12pp.

- ^ McCormack, G., 2007. Cook Islands Biodiversity Database, Version 2007.2. Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust, Rarotonga. http://cookislands.bishopmuseum.org (Accessed 9 Nov 2016).

- ^ Wheeler, W.M., 1942. Studies of neotropical ant-plants and their ants 1. The neotropical ant-plants. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. (Harvard) 90: 3-154.

- ^ Andrade, J. Cardoso de. 1984. Observacoes preliminares sobre a ecoetologia de quatro cole6pteros (Chrysomelidae, Tenebrionidae, Curculionidae) que dependem da Embauba (Cecropia lyratiloba var. nana-Cecropiaceae); na Restinga do Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Rio de Janeiro. Revista Bras. Entomol. 28: 99-108.

- ^ Holthuijzen, A.M.A. and Boerboom, J.H.A., 1982. The Cecropia seedbank in Suriname lowland rain forest. Biotropica. 14: 62-68.

- ^ Vaizquez-Yanes, C. and Smith, H., 1982. Phytochrome control of seed germination in the tropical rain forest pioneer trees Cecropia obtusifolia and Piper auritum and its ecological significance. New Phytol. 92: 477-485.

- ^ Vepsäläinen, V. 1999. The avifauna feeding on fruits of Cecropia angustifolia in a premontane rainforest in the western Andes of Colombia. Thesis, University of Helsinki.

- ^ de Lima, A.L.A., Rodal, M.J.N. and Lins-e-Silva, A.C.B., 2008. Phenology of Tree Species in a Fragment of Atlantic Forest in Pernambuco–Brazil.

- ^ Raphael, M.B., Chong, K.Y., Yap, V.B. and Tan, H.T., 2015. Comparing germination success and seedling traits between exotic and native pioneers: Cecropia pachystachya versus Macaranga gigantea. Plant Ecology. 216(7): 1019-1027.

- ^ Bouaoun, F., 2012. The legendary Cecrops. http://digressiotempus.tumblr.com/post/16976036609/the-legendary-cecrops (Accessed 9 Nov 2016).

- ^ Quattrocchi, U., 1999. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology (Vol. 3). CRC Press.

- ^ Grandtner, M.M. and Chevrette, J., 2013. Dictionary of Trees, Volume 2: South America: Nomenclature, Taxonomy and Ecology. Academic Press.

- ^ The Plant List, 2013. Version 1.1. http://www.theplantlist.org/ (Accessed 9 Nov 2016).

- ^ ITIS Report, 2011. Cecropia pachystachya Trécul. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=822758#null (Accessed 9 Nov 2016).

- ^ Wu, Z.Y., Monro, A.K., Milne, R.I., Wang, H., Yi, T.S., Liu, J. and Li, D.Z., 2013. Molecular phylogeny of the nettle family (Urticaceae) inferred from multiple loci of three genomes and extensive generic sampling. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution. 69(3): 814-827.

- ^ Hadiah, J.T., Conn, B.J. and Quinn, C.J., 2008. Infra-familial phylogeny of Urticaceae, using chloroplast sequence data. Australian Systematic Botany. 21(5): 375-385.

- ^ Sytsma, K.J., Morawetz, J., Pires, J.C., Nepokroeff, M., Conti, E., Zjhra, M., Hall, J.C. and Chase, M.W., 2002. Urticalean rosids: circumscription, rosid ancestry, and phylogenetics based on rbcL, trnL-F, and ndhF sequences. American Journal of Botany. 89(9): 1531-1546.